We use Cookies. Read our Terms

- News

- "We cannot address climate change in a silo"

"We cannot address climate change in a silo"

Photo: Nok Lek/Shutterstock.com

As director of Drawdown Lift, Kristen P. Patterson is in charge of finding practical solutions. In our interview, she explains that implementation is the key to success.

OPEC Fund Quarterly: You focus on practical solutions through the Drawdown Lift program that you are heading. How does your approach work?

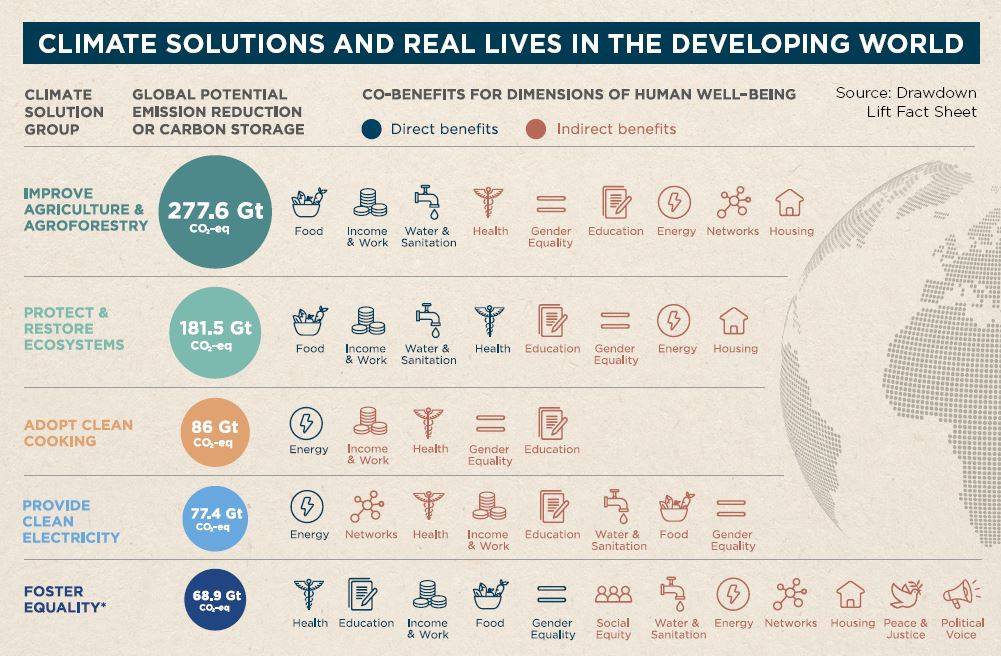

Kristen P. Patterson: We focus on climate solutions that also address extreme poverty and lead to enhanced human well-being. We synthesize knowledge and provide evidence demonstrating how our solutions can contribute to advancing and improving human well-being. We share that knowledge with leaders and policy makers and encourage them to prioritize climate solutions that not only contribute to alleviating poverty but also are aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Increasingly, people are realizing that we need to address climate change as part of achieving these goals.

OFQ: Your position appears to be quite different from the often bleak warnings in the climate debate.

KPP: Yes, Project Drawdown takes a different approach. People have had enough of doom and gloom. We know that climate change is happening, and we have solutions and what we need to do is deploy them at scale. It’s also not a matter of waiting for our governments. Action can be taken at every level so that together we can achieve drawdown faster. To date, we have identified almost 100 climate mitigation solutions. What they have in common is that they are readily available and we can deploy them today. They are growing in scale, they are financially viable, they reduce greenhouse gas concentrations, and they have a measurable net positive impact. We categorize three kinds of solutions: The first category emphasizes reducing sources of greenhouse gases and bringing emissions to zero. The second category focuses on supporting what we call “sinks,” like intact forests, which absorb carbon. And the third category revolves around boosting equity and supporting societies, largely through increasing access to quality education and healthcare.

Source: Drawdown Lift Fact Sheet

OFQ: You are highlighting the interdependence between climate action and human well-being. Do we have capacity for both?

KPP: I worked in the eastern forests of Madagascar for a couple of years, in communities that are isolated from the rest of the world. A woman living there does not wake up and say, ‘OK, today I’m going to focus on my healthcare and tomorrow I’m going to think about my livelihood, and the next day I’m going to fix my family’s home that was damaged by a recent cyclone.’ The reality is that people live their lives in integrated, holistic ways, and therefore it doesn’t make sense to think that we can address climate change in a silo, separate from, for instance, addressing poverty.

OFQ: But doesn’t this add further trillions of cost to the other trillions we also don’t have?

KPP: The cost of action pales in comparison to the cost of inaction. We did rough estimates and found that implementing the set of Project Drawdown solutions yields net operational savings of four to five times the cost of inaction. We estimated the cost of implementation at US$22-28 trillion versus US$95-145 trillion as the cost of inaction. And helping people recover from climate-magnified disasters is enormously expensive.

OFQ: Energy transition and bridging the gap between energy access and climate action is very important to the OPEC Fund. How do you address the issue?

KPP: We are following three approaches. The first approach involves building resilience to climate risks through adaptation. The second approach focuses on accelerating the transition to a low emission economy. And the third approach prioritizes strengthening partnerships. Energy poverty hits on all three themes, because people who don’t have access to electricity are less resilient to shocks. Providing clean electricity can really boost multiple aspects of human well-being.

OFQ: How are you helping companies to move from the net offset approach which has become increasingly controversial?

KPP: Offsets do have a role as part of the energy transition, but they need to be used wisely, sparingly, and without distracting us from the real job — which is reducing emissions by transitioning away from fossil fuels and moving toward renewable energy sources. It’s OK for me as an individual if I want to offset my flight from Washington DC to California, but the reality is that I need to just be flying less instead of offsetting my emissions. Companies need to have the same approach. If the offset payments are used to fund climate solutions in low- and middle-income countries – such as enhanced solar, clean cooking, or protecting nature in ways that benefit people – that’s better than, for example, doing an offset in a forest that was already protected. The key message is that the idea that big companies can simply use offsets to reach net zero is just not true.

OFQ: How do we make sure that climate solutions survive cataclysmic events or bad faith actors?

KPP: Climate solutions aren’t immune to cataclysmic events like the COVID-19 pandemic. However, consumers, companies, and individuals can drive change, and we’ve seen that. In highincome places like the USA and European countries, the private sector and individuals are taking steps to reduce their emissions by installing solar or heat pumps, for example. People are choosing to drive less or walk or ride bikes more, and when they do have to buy a vehicle, more people are replacing old vehicles with an electric vehicle or a hybrid. I have also seen a lot of people changing their diets to be more plant-centered and making changes like wasting less food and composting food scraps.

People might think, ‘Oh, those are just small actions.’ But if you have hundreds of thousands and millions of people taking those actions around the world, it does drive change. I think there’s almost an obligation for those of us who live in high-income countries who have the means to do so to urgently reduce our emissions because we need to allow more space for people and communities in low- and middle-income countries to grow their economies. It needs to balance out as we strive to limit global temperature increases.

OFQ: A lot of the climate discussion in the last six months has been shaped by the war in Ukraine and the deepening energy supply crisis.

KPP: The impact of the war in Ukraine has been enormous, and extends well beyond Europe. I think recent disasters have convinced people of the need to act on climate, and reminded everyone that we need to do more and not less. COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh is a great opportunity for the world to reinvigorate our commitment to the Paris Agreement and go beyond to ensure low- and middleincome countries have the necessary resources to deal with the climate crisis.

OFQ: What would you consider a good outcome of COP27?

KPP: High income nations made a commitment at the COP in Copenhagen in 2009 that by 2020 they would be providing US$100 billion a year to help with climate adaptation and mitigation in low- and middle-income countries. That has never been fully realized, and it’s becoming increasingly apparent how important that funding is. With the next COP taking place on the African continent, I think that the Egyptian presidency realizes the importance of reinvigorating discussions around climate finance, and ensuring that it is additional to existing ODA (official development assistance) funds.

OFQ: Well, is there any good news you would like to share?

KPP: I’m inspired by the women leaders who are now active in the climate movement. I’m also inspired by youth leaders, especially from African countries who are really stepping up, and I am heartened by the fact that the voices of people who are really driving change, like Vanessa Nakate (left) from Uganda, are getting heard more and more. On a more practical level, I would like to mention one of my favorite Drawdown solutions named Multistrata Agroforestry, which I enjoy putting into practice in my small yard and garden. There are many things that can give us hope and keep us inspired.

Kristen P. Patterson

Director, Drawdown Lift

Kristen P. Patterson is the inaugural director of Drawdown Lift, the “engine room” of Project Drawdown, dedicated to efforts to advance climate solutions that also boost human well-being and alleviate poverty in emerging economies. Prior to her current role, Kristen worked for PRB, a nonpartisan research organization focused on improving the health and well-being of people globally. She was a founding member of the Africa Program at The Nature Conservancy, worked in Madagascar as a USAID Population-Environment Fellow, and served as a US Peace Corps volunteer in Niger in the mid-1990s.

Kristen holds a Master in Public Health from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and a Master of Science in Biology and Sustainable Development as well as a Certificate in African Studies from the University of Wisconsin- Madison. She is an alumna of the University of California, Berkeley Beahrs Environmental Leadership Program.

PROJECT DRAWDOWN

Project Drawdown is a nonprofit organization based in the United States that seeks to help the world reach “drawdown”—the future point in time when levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere stop climbing and start to steadily decline. Founded in 2014, the organization works with governments, businesses, academia, and NGOs to develop climate solutions and facilitate their implementation. Working through programs such as Drawdown Labs and Drawdown Lift, the organization currently lists 93 climate solutions ranging from A for Abandoned Farmland Restoration to W for Water Distribution Efficiency. These solutions serve Project Drawdown’s mission which is “to help the world reach drawdown as quickly, safely, and equitably as possible.”

MULTISTRATA AGROFORESTRY

Multistrata agroforestry is a cropping system that features layers of carbon sequestering vegetation. One or more layers of crops grow in the shade of taller trees. The structure and function resemble those of natural forests. The layers of trees and crops sequester substantial carbon while producing food and serving the ecosystem.

Source: Project Drawdown: https://drawdown.org/solutions/multistrata-agroforestry