We use Cookies. Read our Terms

- News

- Venezuela’s engraved rocks: a new clue to ancient lives?

Venezuela’s engraved rocks: a new clue to ancient lives?

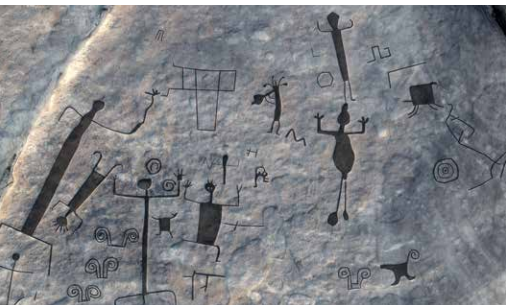

Aerial perspective of east panel at Picure (with interpretative overlay).

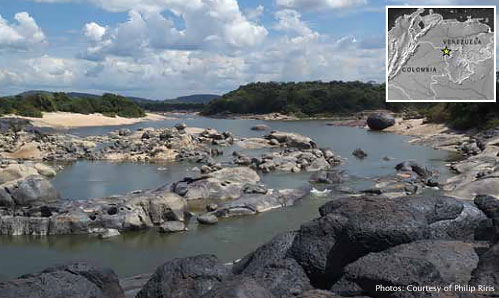

Rock engravings (petroglyphs) located in southwestern Venezuela are among the largest on record anywhere in the world. Newly documented by researchers from University College London (UCL), the engravings are thought to date back up to 2,000 years and provide fresh insight into indigenous life in the region.

Eight groups of engraved rock art, including depictions of animals, humans and cultural rituals, were mapped on five islands within the frequently-flooded Atures Rapids (Raudales de Atures) area of the Orinoco River in Amazonas state.

Drone technology enabled researchers to capture and detail engravings that were otherwise too large or inaccessible to capture. Historically low water levels helped expose some engravings that were previously undiscovered.

The largest panel covers 304 square meters of rock and contains at least 93 individual engravings. One image of a horned snake measures more than 30 meters in length. Another noteworthy panel includes the figure of a flute player surrounded by other human shapes.

Researchers speculate that this depiction may have been part of an indigenous rite of renewal coinciding with the cyclical emergence of the engravings from the river, just before the onset of wet seasons.

The new findings provide a snapshot into ancient lives, according to Dr Philip Riris, lead author of a UCL study published in the December issue of Antiquity magazine.

“While painted rock art is mainly associated with remote funerary rites, these engravings are embedded in the everyday – how people lived and traveled in the region, the importance of aquatic resources and the seasonal rhythmic rising and falling of the waters,” said Riris in a UCL news release.

The Orinoco River stretches over 2,200km from its source in Venezuela’s Sierra Parima Mountains to its mouth on the Atlantic Ocean, traversing biodiverse habitats and shaping the history of more than 26 indigenous peoples.

Atures Rapids, long known as a cultural crossroads, has been the subject of archaeological research for over half a century, but UCL’s study is the first to reveal the extent and depth of connections to other areas of northern South America, including Brazil and Colombia, over the course of two millennia.

Riris stipulates that while none of the rock art has been directly dated, there are clear links between its content and culturally significant beliefs across the pre-Columbian and Colonial periods.

“Their similarity and recurrence along and within waterways suggest that the people responsible for their production shared enduring norms on how to make use of engraved iconography to imbue the landscape with meaning,” writes Riris.

He concludes that: “The diversity of motifs in the sample underscores the centrality of the Middle Orinoco landscape in mediating cultural contact between several regions…It is undoubtedly the work of multiple authors working in significantly different cultural milieu and conditions.”

Researchers are hopeful that their continued study of the rock art can help them better understand the organization, migration patterns and interactions among the region’s pre-Columbian populations.

UCL’s four-year study was funded by the Leverhulme Trust. Fieldwork in Venezuela was made possible by support from the Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Cientificas and Juan Carlos Garcia in Puerto Ayacucho, Venezuela.