We use Cookies. Read our Terms

- News

- Haiti: Local connections bring an energy of their own

Haiti: Local connections bring an energy of their own

OPEC Fund 2020 Annual Award Winner EarthSpark International

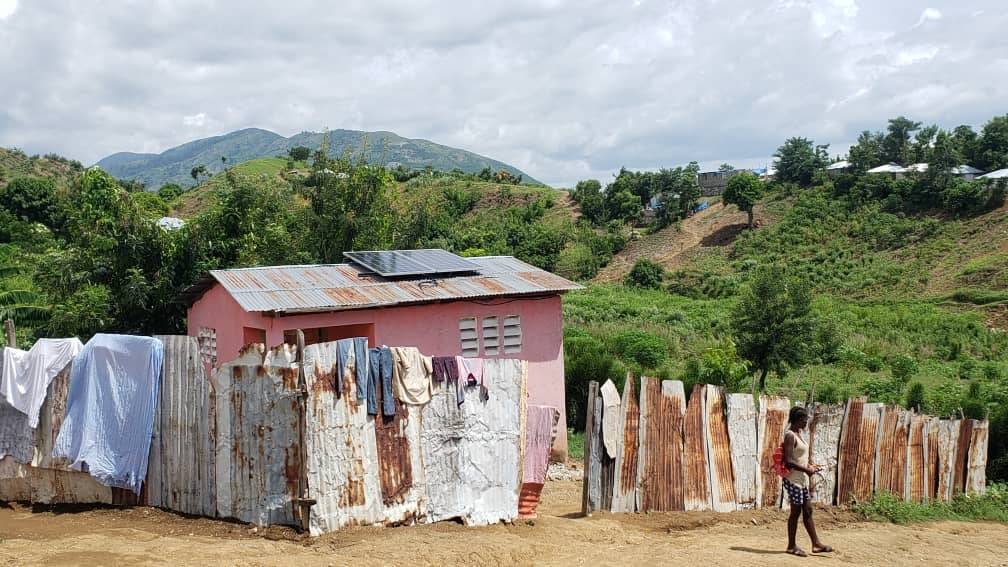

Photo: EarthSpark International

The OPEC Fund has presented its 2020 Annual Award for Development to EarthSpark International, Haiti, in recognition of its innovative approach to energy access and climate change mitigation. Read about the EarthSpark story below…

In 2008, a group of Haitian immigrants living in the US emailed a US cleantech entrepreneur with a proposal: to build a wind turbine to power streetlights in Les Anglais, the small town they came from on the Caribbean country’s south coast.

Seven years later, through EarthSpark International, the non-profit organization created as a result, Les Anglais had more than streetlights. It had Haiti’s first privately operated microgrid, supplying solar-generated electricity to townsfolk who had previously used kerosene, candles and charcoal to meet their energy needs. A second grid opened in the nearby town of Tiburon last year. This mission to solve energy poverty in rural Haiti – where only 15 percent of households are connected to the official grid – is why EarthSpark has been chosen to receive the OPEC Fund for International Development Annual Award for 2020, with a US$100,000 prize.

Les Anglais has changed beyond recognition. Its microgrid – providing 93 kWp of photovoltaic capacity – now serves 493 connections, bringing electricity to more than 2,000 people. Children no longer have to study under streetlights. It is now safer to fetch water late at night from wells (Les Anglais has no piped water). In spite of many recent national challenges, compared to pregrid, the town has a new lease of life, says Wendy Sanassee, Director of EarthSpark’s Haiti operations: “People can have cold drinks. People can watch TV shows in the evening, listen to the radio. Businesses have new machinery. We have restaurants now in Les Anglais. It’s very lively. It’s easier for food vendors to operate at night because customers are going to come [if the streets are lit].”

Beyond these material signs of progress was a subtle psychological shift, which EarthSpark’s President, Allison Archambault, noticed when the grid was switched off during Hurricane Matthew in 2016. “We were hearing from the community that, even without electricity, the grid arriving had changed their sense of self: ‘We are a community that is a leader, a pioneer, and we know we can do things.’”

Les Anglais is certainly that, in both the local and the global sense. EarthSpark aims to build 22 more microgrids across Haiti by 2024 to revolutionize energy access in the country; the prize money from the OPEC Fund award will fund core operations as the organization raises the US$40 million needed to do so (it has just secured US$10 million from the Green Climate Fund). In international terms, interest in the potential of microgrid technology to address energy poverty is growing: there are 6,610 such projects in 2020 (up from 4,475 in 2019), and the microgrid sector is expected to be worth USUS$47.4 billion by 2025 (it’s currently worth US$28.6 billion). Les Anglais is at the forefront of this boom. The smart meter that developed out of the project now has its own separate company, SparkMeter, which has sold over 100,000 meters in more than 25 countries.

EarthSpark is a perfect example of the kind of dynamic local partnership the OPEC Fund seeks out in its mission to help develop partner countries. Since the fund was created in 1976, it has approved loans and donations of more than US$25 billion in sustainable development commitments – to both public entities and private sector partners.

But finding the right partners to achieve development goals in a given country can be challenging. They have to tick specific boxes, as Khalid Khadduri, the OPEC Fund’s Senior Private Sector Investment Manager, explains:

We want to make sure there’s that developmental impact in aligning with what we’re trying to support as an institution, socio-economically and in supporting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). But because you’re taking private-sector risks, there are a lot of other factors you need to look into: the commercial, technical and financial viability, as well as doing the social and environmental due diligence on a project.”

Awarding grants to non-profits and non-governmental organizations is another avenue if the private sector can’t fulfil these requirements for a given territory. Prior to the award, the OPEC Fund had also provided a US$350,000 grant to EarthSpark to develop the second Tiburon grid; with an initial phase producing solar lanterns, and then the microgrid, in Les Anglais, the organization had already demonstrated the ways in which it fulfilled the OPEC Fund’s development brief.

Financial viability was something EarthSpark was “clear-eyed” about from the start, says Archambault. Charging for energy meant challenging Haiti’s culture of non-payment for electricity – with significant amounts of theft from the official grid.

But EarthSpark – enabled by the SparkMeter technology it launched – allows grid users in Les Anglais to prepay, buying electricity credits in small quantities as needed. “It was fundamentally respectful of our customers, instead of surprising them with a bill a month after they consumed the electricity. It just didn’t make sense in those markets,” she says. The upside is that payment efficiency is quite high, theft is low, and many households now connected to the grid are saving up to 80 percent on what they had previously been spending on other means of lighting, phone charging, and other basic energy services.

The Les Anglais microgrid has also energized the local economy, an important part of the OPEC Fund’s mandate to support small- and medium-sized enterprises. No longer relying on diesel-run generators has reduced the cost of everyday business tasks – such as lighting and charging phones – that rely on electricity. And with refrigeration now possible, selling cold drinks has become a popular retail option in the town. Entrepreneurs from carpenters to ice cream confectioners can now plug in to the reliable power.

The concept of “feminist electrification” – EarthSpark’s commitment to this won a UN award in 2018 – is central to the development process. “There’s no secret sauce there,” says Archambault. “It’s just engaging women authentically throughout the entire process of pre-development, development and operations.” She highlights outreach work with Fanm Vayant Zangle, an agricultural cooperative: EarthSpark has helped them source electric-powered labor-saving devices, such as a corn sheller and a mill. Another current project – open to all, but predominantly involving women in Les Anglais – focuses on helping locals transition from charcoal-based to electric cooking.

With EarthSpark on the frontline of renewable technology – another sector of interest for the OPEC Fund, which has supported more than 150 related projects to date – it is well-placed to fine-tune the best model for reliable microgrids. Using its smart-meter capabilities allows it to more precisely gauge demand for electricity; crucial when supply is reliant on variable natural sources, such as solar, and whatever can be stored in batteries (the forthcoming grids won’t have diesel backup generators). “If there’s a new thing that EarthSpark is working on to share with the world, it’s figuring out demand-side management in a way that enables 100 percent solar microgrids to maintain very high reliability at a lower cost than using backup diesel generators,” says Archambault.

The OPEC Fund has been working in Haiti since its inception in 1976, and has approved approximately US$100 million for about 50 development operations. Energy – with its galvanizing effect on agriculture, and on water and sanitation – remains key for development there. However, the government’s interest is currently also being drawn towards the agricultural sector, which has withstood the effects of the pandemic better than others; the OPEC Fund is negotiating funding for a large-scale irrigation project in the south of Haiti.

But the country – the poorest in the western hemisphere, where half the population live on less than US$1 a day, and with turbulent governance – remains a challenging environment in which to operate. Its vulnerability to natural disasters such as the devastating 2010 earthquake and 2015 Hurricane Matthew is especially problematic, says Natalia Salazar, the OPEC Fund’s Country Manager for Haiti: “What they cause is delays. Our project implementation average worldwide is seven years, but in Haiti it can take over 10. And in that time, you might have three different governments.”

Even with the government’s interest in the energy sector, and broad support for microgrids, Archambault says the lack of a legal and regulatory framework in Haiti makes it slow-going for initiatives such as EarthSpark’s. There was no electricity regulator when it was developing the Les Anglais grid; the local municipality had to grant the right to build the system. Tiburon’s is the new regulatory body’s first official microgrid concession.

Partly because of such obstacles, the OPEC Fund has yet to fund private sector companies in Haiti. But its work with the public sector is vital for the capacity-building that will eventually allow this to happen – especially in the country’s poorer south. “It shows that there’s a will,” says Salazar. “By supporting rural areas, you can support a whole community, you can lift people out of poverty, and you can provide know-how and solutions to the government.”

The OPEC Fund award is testament to what EarthSpark has contributed so far. In a matter of months, ice-cold drinks are set to clink under microgrid-powered lights at the launch of the next EarthSpark microgrid, whetting the appetite for all this can bring. Archambault says it again: “There really is this idea that Les Anglais proved what was possible. We’ve been ‘derisking by doing’ here by innovating, by pushing forward, by working together. Now it’s time to scale up.”

The OPEC Fund’s Annual Award was introduced in 2006 and comprises a US$100,000 prize to recognize an individual or organization demonstrating excellence in poverty reduction and sustainable development. Bestowing this year’s Annual Award for Development to EarthSpark International will help highlight the urgent need to support Small Island Developing States in addressing these important goals and demonstrates the commitment of the OPEC Fund to supporting developing countries in their pursuit of social, environmental and economic progress.

Related Stories

Notice that after activation data will be sent to Youtube.

Read our Terms.