We use Cookies. Read our Terms

- News

- Build back better

Build back better

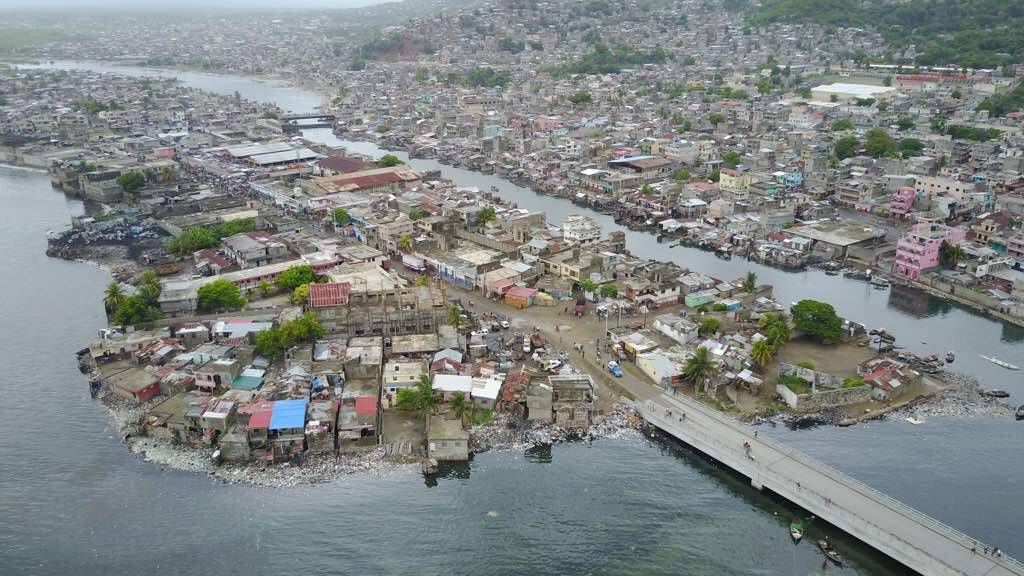

Haiti. Photo: UNDP

Natural disasters do not exist, argues Jessica Faieta, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Director for Latin America and the Caribbean. Natural hazards become disasters when people, communities and societies are vulnerable to them.

Reducing risks related to disasters has never been more urgent – and the Latin America and the Caribbean region bears witness to this. Seven hurricanes have hit the Caribbean in recent months, two of them as category five, causing catastrophic damage, including in countries that were still recovering from another massive hurricane that struck one year ago.

Also, two earthquakes rocked Mexico in September – with almost 5,000 aftershocks – while another powerful quake struck Ecuador in April 2016. In addition, both Colombia and Peru suffered major landslides in the past eight months.

The number of children, women and men killed is deeply saddening, especially in an era in which we have the knowledge to minimize loss of lives due to natural events. Yet, we keep experiencing tragedies. The fact is that natural disasters do not exist. Natural hazards become disasters when people, communities and societies are vulnerable to them. This, in turn, translates into losses – of lives and assets. And the poorest are the hardest hit.

On the one hand, poverty reduces people’s capacity to face and recover from disasters; on the other hand, disasters also hinder people’s ability to leave poverty behind.

That’s why if the world is to end poverty in all its forms by 2030 we must boost resilience – in all its forms. This means the capacity to cope with shocks without major, long-term economic, social and environmental setbacks.

A disaster of natural causes, a financial crisis, an economic slowdown or a health problem in the family can all cause people to fall into poverty – especially those who barely managed to leave it behind. To help absorb the impact, people need a ‘cushion’, such as social protection systems or physical assets.

In this particular moment, it is crucial to take special notice of what the Caribbean is experiencing. Two back-to-back hurricanes, Irma and Maria, were the most powerful ever recorded over the Atlantic. They forced – for the first time ever – the island of Barbuda to evacuate its entire population.

These colossal storms battered several Caribbean countries with deadly waves and maximum sustained winds of nearly 300 km/h for up to three full days. They decimated Barbuda, Dominica and Saint Maarten, also impacting some of the region’s disaster preparedness champions, like Cuba and the Dominican Republic.

What we have just witnessed is a game changer. And it will likely be the new norm. That’s why we need urgent action.

It’s a fact. Climate change – and all natural hazards – hit Small Island Developing States (SIDS) hard, even though these countries haven’t historically contributed to the problem. Having lived and worked in four Caribbean countries I have witnessed first-hand how such nations are extremely vulnerable to multiple challenges ranging from debt and unemployment to climate change and sea level rise.

Clearly, if countries do not reduce their vulnerabilities and strengthen their resilience – not only to natural disasters but also to any shock – we won’t be able to guarantee, let alone expand, progress in the social, economic and environmental realms.

Since the hurricanes hit, we have been working on the ground in affected Caribbean countries supporting governments to build back better – with more resilient communities – so they are prepared for the next hurricane season only eight months ahead. This is essential: international cooperation and the private sector play a key role with investments in resilient infrastructure.

If Caribbean countries are to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in 13 years they need urgent access to financing – including for climate change adaptation. However, the vast majority of Caribbean SIDS are ranked as middle-income countries – with per capita income levels above the eligibility benchmark – and are shunned from receiving concessional financing for development.