We use Cookies. Read our Terms

- News

- Are the Sustainable Development Goals becoming own goals?

Are the Sustainable Development Goals becoming own goals?

After good progress, the Sustainability Agenda has lost most of its momentum and, in crucial areas, has even been sliding backwards.

If this were an inspirational sports movie, now would be about the time our defeated protagonists would be trudging into the locker room while our coach gives a rousing pep-talk that turns things around for a second half win. However, those hoping for an 11th-hour Hollywood ending for the successful completion of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will likely walk out of the cinema disappointed.

Instead of that come-from-behind victory that both ends human hardship and gets a handle on harmful emissions, we get “an epitaph for a world that might have been.”

That grim phrase opens the recently released The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition, along with other doomsayer gems like “promise in peril” and “sound the alarm”, among many other signs that all is very far from well as the world reaches the SDG midpoint. The document does not mince words about the lackluster progress towards the framework the UN hoped would lift the world out of poverty and ensure the world’s 8 billion people can grow in a sustainable, climate-friendly way.

The SDGs were adopted in September 2015 as part of the UN’s 2030 Agenda, building on an earlier set of much narrower global goals, the eight Millennium Development Goals. The new 17 objectives, containing 169 smaller targets, were going to be challenging to achieve on their own, but they promised a new way forward to a world that left no one behind. That was before the COVID-19 pandemic, a fragile world economy, global supply chain disruptions, the war in Ukraine, tens of millions of displaced people, and a smattering of climate-related events of increasing frequency that give us the first real taste of what a warming world could look like.

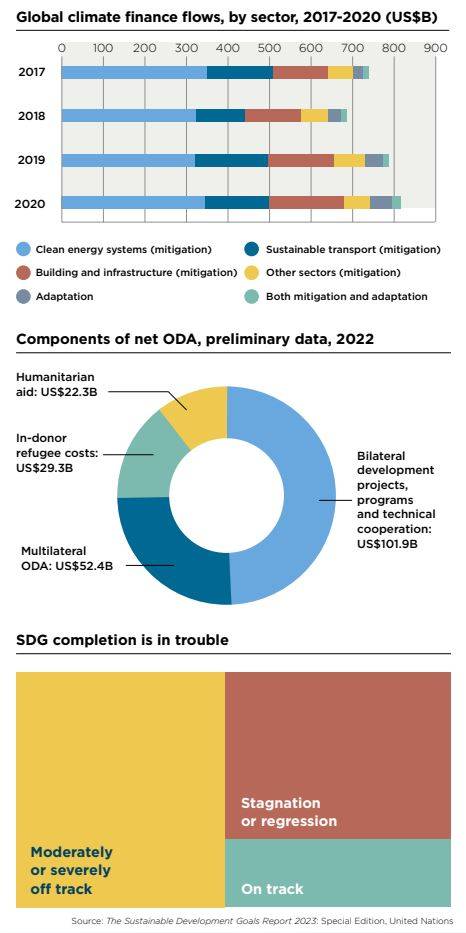

Now, with only seven years left before the deadline, the news is, to put it mildly, not great. Of the 140 SDG targets for which data is available, progress is weak on about half and about a third have stalled or gone in reverse. A mere 15 percent of the targets are actually on track.

Some developing countries are struggling to even maintain stagnation on their goals, with many seeing early gains slipping backwards. For example, SDG 14 – Life Below Water’s Ocean Health Index is one particular area that has seen decreases in many countries. Even countries that have seen the most progress towards achievement still have long ways to go.

First, the bad news

Taking a deeper look at the individual goals gives a picture at what the world will look like in 2030 if current trends continue. Kicking things off with SDG 1 – End Poverty, an estimated 575 million people will still be living in extreme poverty, in other words, living on less than US$1.25 per day.

Billions are without safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene, making the completion of SDG 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation especially challenging. For example, reaching safe drinking water targets will require a six-fold increase in global progress. The raw numbers for this particularly critical goal are also sobering; 2.2 billion people lacked basic handwashing facilities in 2022. In 2020, 2.4 billion people lived in water-stressed countries.

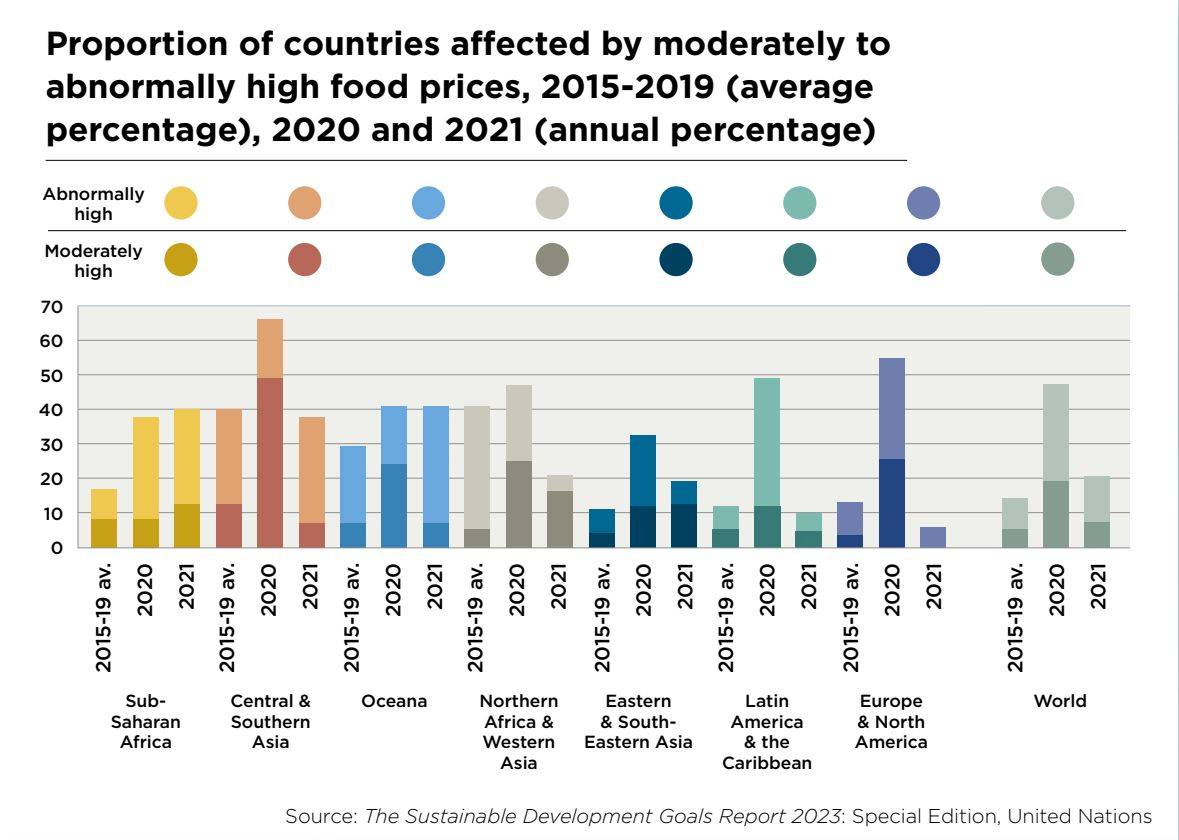

The statistics on food security are equally stark. With a projected 600 million plus worldwide facing hunger in 2030, hitting the target for SDG 2 – End Hunger is not hopeful. Following a spike in 2020, food prices have come down but are still above the average from previous years. Increased demand; rising energy, fertilizer and transport costs; supply chain disruptions and trade policy changes have all contributed to sustained price increases. Additionally, sub-Saharan Africa and least developed countries (LDCs) face additional challenges of worsening security conditions, macroeconomic difficulties and a high dependency on imports. While the report’s data ends in 2021, the start of the war in Ukraine in 2022 led to a new price hike and further global food insecurity with dramatic consequences especially for the most vulnerable countries.

Elsewhere, many goals require closing a steep financing gap in order to enable completion. Seventy-nine low and lower-middle income countries need an average of US$97 billion for SDG 4 – Quality Education. International public financing for clean energy for developing countries (a component of the energy-themed SDG 7) has further declined to US$10.8 billion, down by more than half since 2017’s level of US$26.4 billion. Developing countries will need nearly US$6 trillion in climate financing by 2030 in order to hope to complete SDG 13 – Climate Action.

On the environmental front, the situation is serious. Due to deforestation, land degradation, pollution and other forms of environmental destruction the world is facing the largest species extinction event since the dinosaur age. The world’s temperature increase is expected to exceed the 1.5°C tipping point by 2035 unless “deep, rapid and sustained” greenhouse gas emission reductions are made.

...but it’s not all bad news

That’s not to say there haven’t been bright spots. Global electricity access has risen from 85 percent in 2015 (the launch of the SDGs) to 91 percent in 2021 and renewables account for 30 percent of energy consumption. Over that same time period, governments are spending proportionally more on essential services such as education, health and social protection.

SDG 3 – Good Health and Well-being has seen several positive outcomes so far. One hundred forty-six countries or areas have already met or are on track to reduce the under-5 years mortality target to a minimum of 25 deaths per 1,000 live births. Effective HIV treatment has cut global AIDS-related deaths by 52 percent since 2010. Also, 47 countries have eliminated at least one neglected tropical disease.

Spending on refugees in donor countries and aid to Ukraine has helped push net Official Development Assistance (ODA) up to US$206 billion last year, an increase of 15.3 percent from 2021. This helped explain why roughly a quarter of 2022’s ODA was for humanitarian aid and refugee spending (see chart on page 45). Foreign aid plays a critical role in developed countries assisting more vulnerable developing countries. In line with the relevant SDG indicator, ODA providers are encouraged to set a target of at least 0.2 percent of gross national income to LDCs. For comparison, Sweden’s 0.3 percent surpassed the recommended rate, while other EU and North American countries like France, Germany and the USA, the world’s largest economy, earmarked only 0.1 percent of their gross national incomes to LDCs in 2021.

In addition to that progress, data and monitoring became more robust, with more than 2.7 million data records in the SDG global database in 2023, compared with only 330,000 in 2016. Data capacity developments are key and closing data finding gaps are necessary in order for LDCs, in particular, to have an accurate way to measure and manage data to support effective policy-making.

A significant second half

With the stakes and progress (such as it is) spelled out, where to begin to make the necessary changes as the 2030 deadline approaches? The report calls on governments to redouble their efforts and their investment in sustainable development (both at home and abroad). These are all easier said than done.

As with many things, money makes the Goals go round. An SDG stimulus plan, detailed in the UN’s report, calls for an additional US$500 billion per year in financing for three main areas of action. First, tackle the high cost of debt. Second, scale-up affordable long-term development financing, especially through multilateral development banks. Third, expand contingency funding to all countries in need. By reforming the international financial architecture and securing a financing surge, the report reasons, the results will be mutually reinforcing.

Other proposed solutions prioritize sub-components of the SDGs themselves: close divides to leave no one behind, secure food, water and renewable energy systems, and prevent new and existing disaster risks.

As the report makes clear, we know the outcome of business as usual. By not making the next seven years to 2030 count, we will never know the “world that might have been.”

5 ways to improve

The clock is ticking but the UN says there is still time to turn things around...

- Heads of state and government should recommit to seven years of accelerated, sustained and transformative action.

- Governments should advance policies and actions aimed at poverty and inequality reduction, the protection of nature, and the empowerment of the most vulnerable.

- Governments should strengthen capacity, accountability and public institutions.

- The international community should mobilize the resources and investment for developing countries to achieve the SDGs.

- UN member states should strengthen and boost the UN development and multilateral systems.